Waterfowl and Waterbirds

Long-term gains level off, renewing conservation concerns

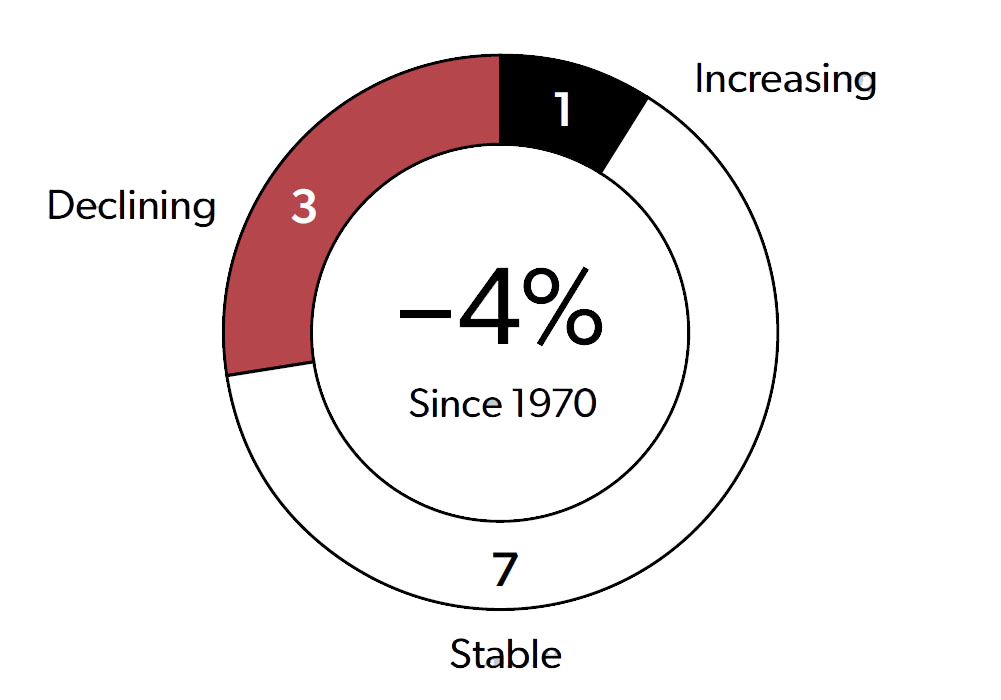

In past State of the Birds reports, waterfowl and waterbirds were the only groups that showed population gains, with waterfowl showing the greatest increases. Duck populations now are 24% higher than they were in 1970—the result of foundational policies (such as the North American Wetlands Conservation Act, Duck Stamp program, and Conservation Title of the Farm Bill) that have long safeguarded wetland resources and associated habitats.

But today this legacy is in jeopardy. Loss of wetlands and grasslands is accelerating in key regions for waterfowl, and wetland protections are being weakened. Environmental and land-use changes are driving recent duck and marsh bird declines in many areas. Protecting America’s waterfowl and waterbird conservation legacy means living up to the policy pledge of no-net-loss of wetlands and delivering creative solutions that provide diverse benefits to wetland birds, agricultural producers, and broader society.

No-Net-Loss-Wetlands Policy Is Not Being Achieved

Bipartisan support for a “no-net-loss” of wetlands federal policy has been strong since it was first announced by President Bush in 1989. Yet the latest U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wetlands Status and Trends report shows that the annual rate of wetlands loss increased by more than 50% over past decades, with a staggering 670,000 acres of net loss among the vegetated wetlands that are crucial to the nation’s ecological health.

The main drivers of wetlands loss include drainage and filling for agriculture, development, and silvicultural operations. Rebuilding America’s wetland complexes begins with defending the wetlands policy protections that remain. In particular, the Swampbuster provision of the Farm Bill has been vital to retaining wetlands and supporting populations of waterfowl, waterbirds, and shorebirds in agricultural landscapes.

The long-term resiliency of duck populations and other wetland birds absolutely depends on keeping a strong base of wetlands intact.

Dabbling and Diving Ducks

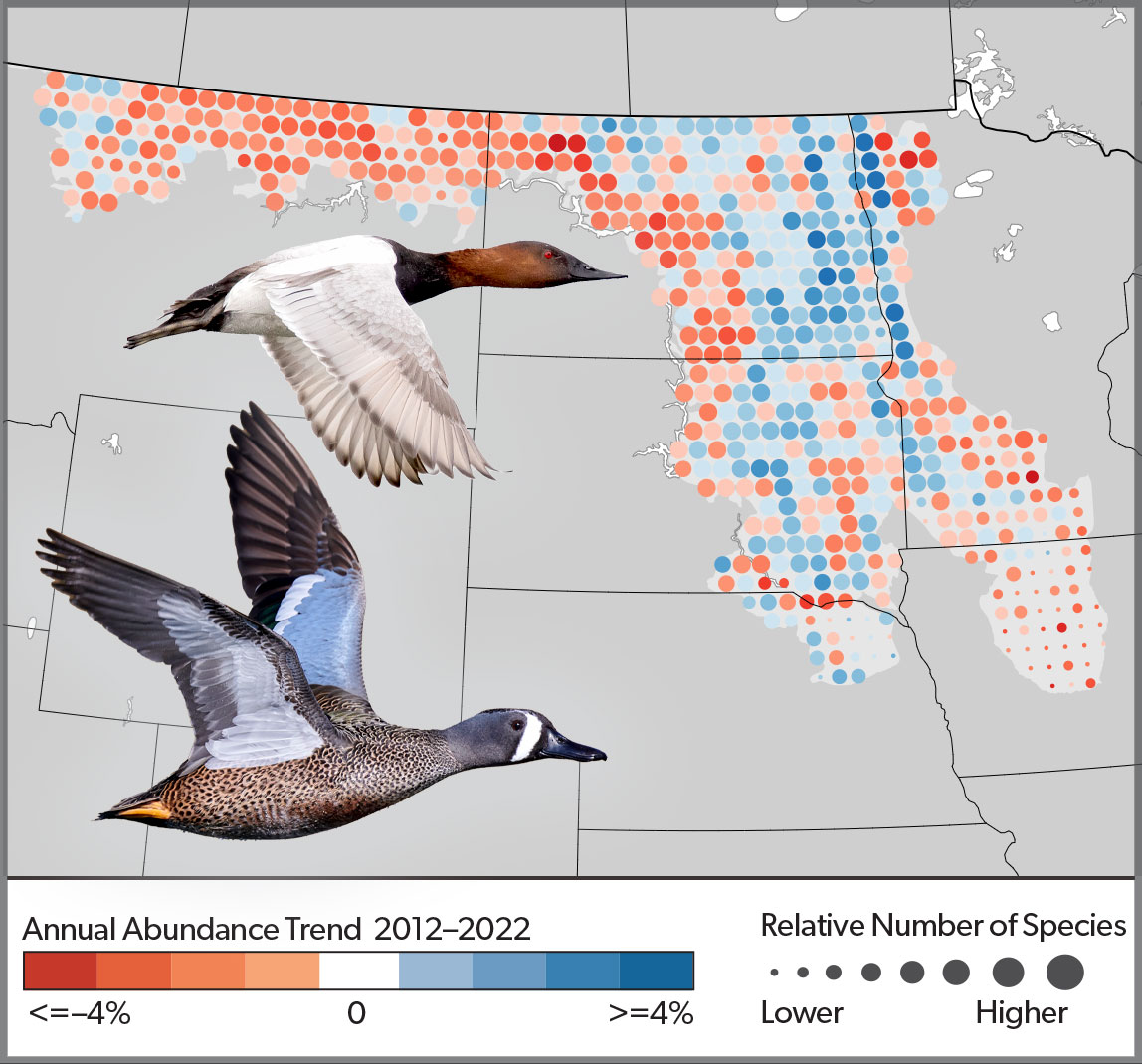

The Prairie Pothole Region (PPR) is North America’s most important area for breeding ducks, supporting as much as two-thirds of the continental population. But over the past decade duck populations in the PPR have declined and are now 10% below the long-term average.

Many waterfowl rely on grassland–wetland habitat complexes for breeding. The combination of grassland and wetland loss in the Dakotas and Montana is rolling back decades of waterfowl population gains built by conservation policies such as the federal Duck Stamp and North American Wetlands Conservation Act. Blue-winged Teal by Sharif Uddin / Macaulay Library; Canvasback by Caroline Lambert / Macaulay Library.

-

Duck Breeding Habitat at Risk

Recent duck declines in the Prairie Pothole Region (PPR) correspond with a period of deteriorating environmental conditions and unrelenting wetland and grassland loss, driven by the expansion and intensification of row-crop agriculture and erosion of wetland protections.

-

Farm Bill Conservation Programs Can Boost Ducks

Voluntary conservation programs implemented via the Farm Bill, such as the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), have proven successful in supporting duck populations. But CRP acres have declined by half across the PPR since 2007.

-

Voluntary Conservation Is Popular in Farm Country

More than 7 in 10 farmers support expanding voluntary conservation programs to provide financial support for healthy farms. Local communities benefit, too, as PPR wetlands conserved by Farm Bill programs† capture billions of gallons of floodwaters.

† U.S. Geological Survey. 2008. Ecosystem services derived from wetland conservation practices in the United States Prairie Pothole Region with an emphasis on the U.S. Department of Agriculture Conservation Reserve and Wetlands Reserve Programs.

American Black Duck

American Wigeon

Black-bellied Whistling-Duck

Blue-winged Teal

Canvasback

Cinnamon Teal

Common Merganser

Fulvous Whistling-Duck

Gadwall

Greater & Lesser Scaup

Green-winged Teal

Hooded Merganser

Mallard

Mottled Duck

Northern Pintail

Northern Shoveler

Redhead

Ring-necked Duck

Ruddy Duck

Wood Duck

Sea Ducks

Across the expansive range of sea ducks, from the Arctic tundra to seacoasts and the Great Lakes, rapidly warming waters are affecting crucial food resources. One-third of sea ducks are Tipping Point species, including Steller’s, Spectacled, and King Eider, as well as Black Scoter and Long-tailed Duck.

Christmas Bird Count (CBC) numbers for Common Eiders are declining along the Northeast coastline, as eiders shift their wintering range away from the Gulf of Maine—where water temperatures are warming at nearly three times the rate of global oceans. This eider population shift increases the importance of other key sea duck habitat sites along the Atlantic Coast. Common Eider by Jeremiah Trimble / Macaulay Library.

-

Protecting Nearshore Coastal Habitats Is Crucial

The Sea Duck Joint Venture has identified 85 key habitat sites essential for sea duck populations. These critical habitats are at risk from warming ocean temperatures, wind energy, shipping, commercial fishing, aquaculture, and other industrial development.

-

Indigenous Partnerships Can Strengthen Conservation Efforts

There is an important opportunity for tribal partnerships in sea duck conservation, as many sea duck species are culturally significant to Indigenous peoples and can enhance food security for northern communities.

-

Improved Sea Duck Monitoring is Greatly Needed

Scientists need reliable data to understand sea duck population declines and distributional changes, and to inform innovative solutions to help sea ducks survive in the changing oceans and northern habitats of the future.

Barrow’s Goldeneye

Black Scoter

Bufflehead

Common Eider

Common Goldeneye

Harlequin Duck

King Eider

Long-tailed Duck

Red-breasted Merganser

Surf Scoter

White-winged Scoter

Waterbirds

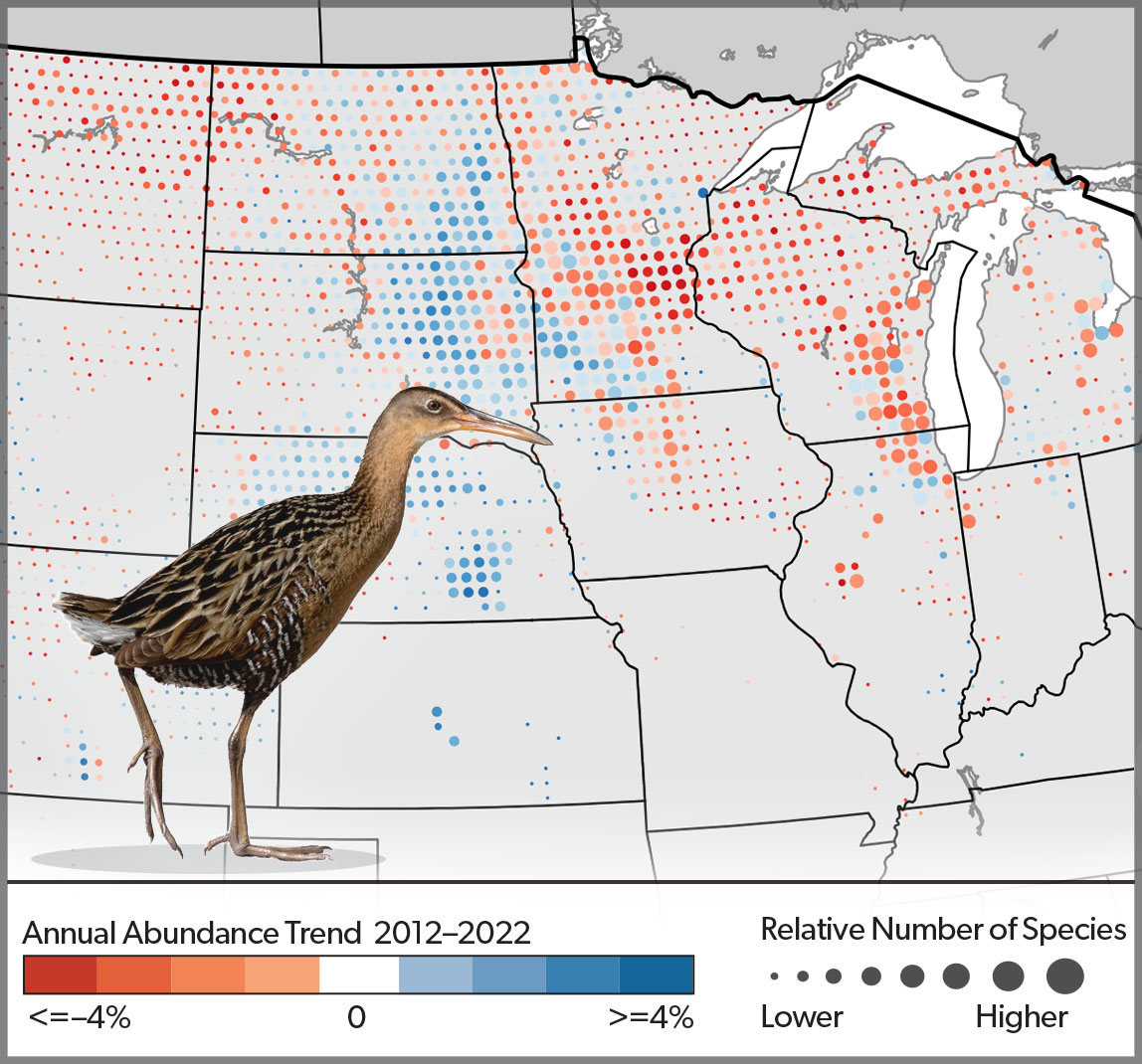

The upward trend for the waterbirds group is driven by growing populations of fish-eating species, such as pelicans—a testament to the lasting impact of the Clean Water Act. But more than a third of waterbird species are declining. Secretive marsh birds, such as King Rail and Black Rail, are affected by the loss of vegetated wetlands.

Declines among secretive marsh birds are occurring in the Upper Midwest. Alternative strategies for remaining wetlands, many of which are actively managed for high-quality duck habitat, could provide shallow water and robust vegetation and benefit marsh birds while continuing to support duck populations. King Rail by Jeremiah Trimble / Macaulay Library.

-

Wetlands Management Needs to Do More for Birds

Given significant wetlands losses, creative management strategies are needed to ensure the nation’s shrinking wetlands can support broad suites of wetland-dependent birds, including waterfowl and secretive marsh birds.

-

Proactive Management Can Avoid ESA Listings

More inclusive wetland management strategies can help keep at-risk wetland species such as King Rail off endangered species lists, thereby avoiding expensive regulations and litigation. The Eastern Black Rail was recently listed due to habitat loss.

-

Wetlands Can Benefit Every Bird and Everybody

Holistic wetlands management, delivered at larger scales, promotes full ecosystem health. Healthier wetlands deliver added benefits to people, including clean, abundant water and reduced flood risks.

American Bittern*

American Coot

American Herring Gull

American White Pelican

Anhinga

Black Skimmer

Black Tern

Black-crowned Night Heron

Bonaparte’s Gull

Brown Pelican

California Gull

Caspian Tern

Clapper Rail*

Common Loon

Common Gallinule*

Common Tern

Double-crested Cormorant

Eared Grebe

Forster’s Tern

Franklin’s Gull

Glaucous Gull

Glaucous-winged Gull

Glossy Ibis

Great Black-backed Gull

Great Blue Heron

Great Cormorant

Great Egret

Green Heron

Gull-billed Tern

Heermann’s Gull

Horned Grebe

King Rail*

Laughing Gull

Least Bittern*

Least Grebe

Least Tern

Limpkin

Little Blue Heron

Neotropic Cormorant

Pacific & Arctic Loon

Pied-billed Grebe

Purple Gallinule*

Red-necked Grebe

Red-throated Loon

Reddish Egret

Ring-billed Gull

Roseate Spoonbill

Royal Tern

Sandhill Crane

Sandwich Tern

Short-billed Gull

Snowy Egret

Sora*

Tricolored Heron

Virginia Rail*

Western Cattle-Egret

Western & Clark’s Grebe

Western Gull

White Ibis

White-faced Ibis

Wood Stork

Yellow-billed Loon

Yellow-crowned Night-Heron

*The 8 starred species were used in the eBird Trends analysis of secretive marsh birds (above).